'They know me there.'

This post is copied over from my new Substack account; follow me over there, it's a bit fresher I think.

I can’t remember what he asked me exactly, as he picked up his pen and held it expectantly over a sheet of paper — the back of my appointment form, stapled to a printout of my bared teeth in reverse chromatic flash. I think it was something broad, like ‘tell me what’s going on’, or ‘tell me about yourself’… No, it was specifically to do with medical conditions, inviting me to share anything I felt he needed to know going in (-to my mouth, potentially), because I fell into the trap and automatically offered my usual clichéd quip, ‘how long have you got?’

My therapist would cringe when I told her that the next day.

This surgeon just smiled, and told me he wanted to know as much as possible. I started from the top, which I don’t usually do, but I suppose after rolling out this rusty spiel with wonky wheels for so many years it’s good to try something new.

‘Recently diagnosed with Chronic Fatigue,’ I said, and braced myself for the tears that usually come when I share this new diagnosis — new, but at the same time almost a decade old. But that wasn’t what made me cry, this time anyway. ‘My endocrinologist told me I have it because I had radiotherapy ten years ago,’ I continue, suddenly feeling like I’m giving a flimsy handwritten sick note to a teacher to get out of PE.

He nods, and scribbles his notes. ‘And what was the radiotherapy for?’

‘Brain tumour,’ I almost roll my eyes, because it’s become so boring to me. That old chestnut. I can’t believe it’s a revelation to anyone at this point. The words feel dull in my mouth, like when your chewing gum loses its flavour* but you can’t spit it into a tissue yet. ‘I had two surgeries, then radio. I have a bit left.’ I don’t go into it, because I can’t be bothered.

*chewing gum actually doesn’t ‘lose its flavour’ like you think it does, at least not according to research by the brothers Green on their science bomb-dropping/life advice-giving podcast. It’s partly your mind getting used to the taste, and processing it. And of course, the sugar coating on the tablets or strips coming off on your tongue very quickly. Anyway…

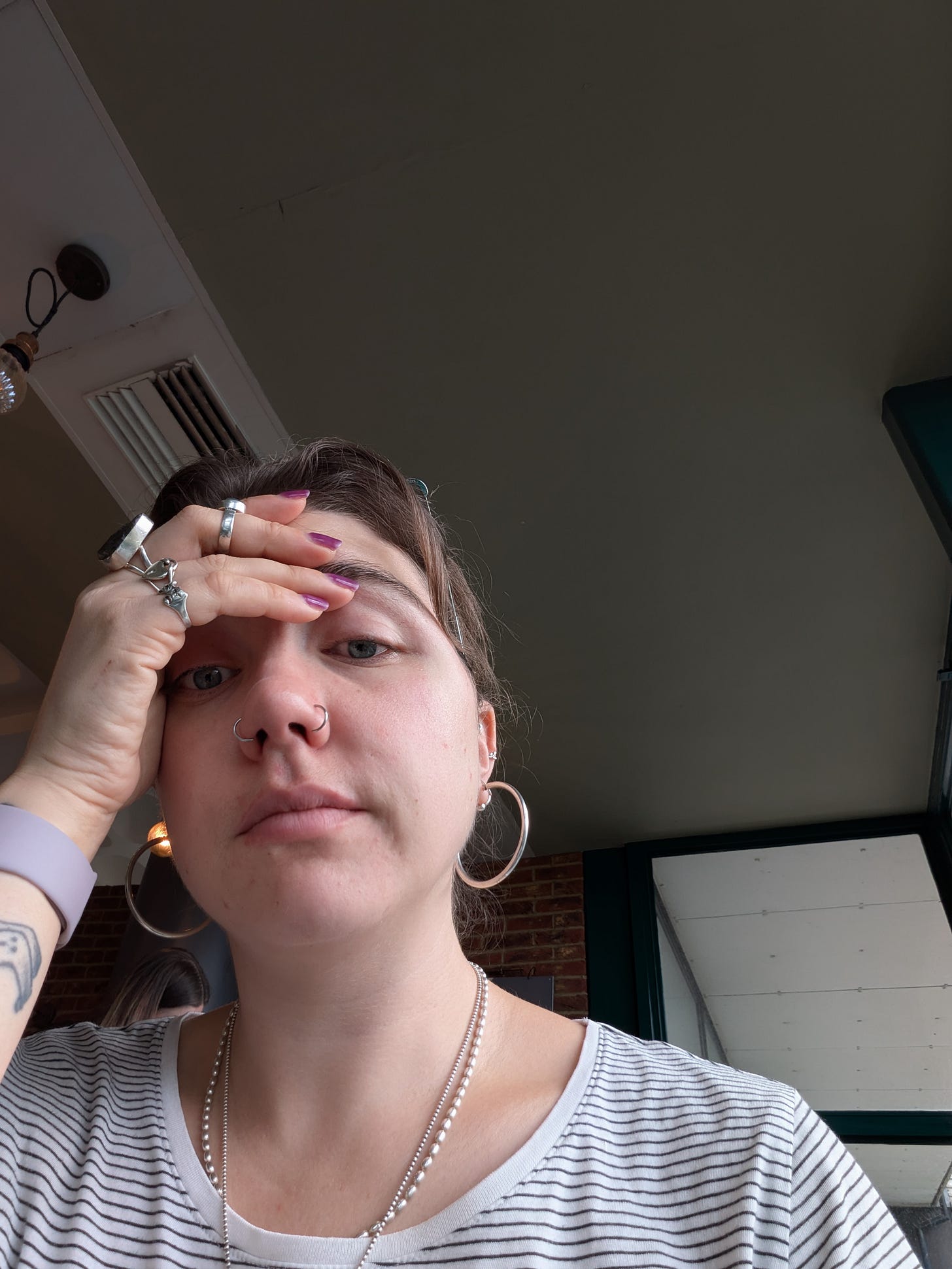

Then I tell him I’ve had two operations on my intestines, and they’re prone to obstructions. I tell him I’m a vegan, so obviously I struggle with low iron levels. I tell him the only medication I currently take is for my under-active thyroid, which my endocrinologist also discovered, two years ago. I tell him I’m awaiting a prescription for ADHD medication, ‘it begins with methyl—?’ and that means I have to explain that I was diagnosed with that three years ago, before it became so popular, and I’m moderate, not just ‘a little bit’. I tell him as much as I can before my voice breaks. This entire time I am very aware of the woman who showed me in, I assume a HCA, sitting on a chair at the other end of the consultation room looking on. I can feel the incredulous empathy and sad kindness rolling off her in waves, stretching across the room towards the back of my head and shoulders, and try not to mistake it for pity. I know she’s shocked, because look at me. I could be any normal 30-something, in baggy denim trousers and a striped t-shirt. I actually look about 27, and I know that’s because I didn’t properly live 5 years of my life.

This is when the tears took their cue. They’d been lurking not too far below the surface anyway, unsurprisingly, as this hospital hosts a rotting pile of my murkiest memories. I’d already run my eyes over the different ward names listed and broken up by floor on the wall next to the entrance, and reached out to tap ‘Richard Ticehurst/SAU’ for luck, and for my past self, writhing in agony at 3am while filling up those stupid little cardboard bowls with ripe brown fluid that doesn’t quite qualify as vomit.

The tears — I acknowledged them, but fought. I blinked furiously, and even did that classic school playground move of rubbing them at their corners and stretching them from side to side like I’ve got dust in my eye or maybe I’m sleepy, nobody can be sure, except everybody knows. This is when the surgeon asked me what I do for a living. I always find this moment quite sweet, like they’re trying to facilitate a normal conversation, when I know there must be some relevance to it, some connection to my health that they need to gauge, otherwise why would they ask? I told him I have three jobs, putting on my ‘what am I like?’ tone of voice I speak in when I know I’m outing myself as too much of a try-hard. I told him what my 9-5 is — ‘oh, is that a beauty brand?’ ‘beauty, yes, but mostly baths’ — then my Saturday job which he is much more interested in and dubs a ‘hobby’ judging from how excited I am about it, and of course my freelance work which I always wish I could do more of. He does more nodding, and noting. I sigh. Then he looks up from his scribbles, and with a completely deadpan face but the brightest, kindest eyes, he asks me —

‘So, when do you live?’

That’s when I started to properly cry. I let the streams flow down my face and cut lines through my neutral powder foundation, without acknowledging them. I mumbled ‘I don’t know’. He told me very gently to make more time for myself, and I agreed while I stared at the wall above his desk, just to my left, hot blotches forming on my wet cheeks as I tried to feign interest in all the laminated information that was irrelevant to me.

He asked if I wanted this surgery. I said I didn’t really, but I also felt that if it would help me later in life, then I might as well. Very open, very sensible, only a hint of honesty — blink and you’ll miss it. What I didn’t say was, I’ve had so many surgeries. I have so many broken parts. I wish it would all just stop.

Then he said that the surgery would take place there, but I’d have to be referred for a scan at East Grinstead. I brightened up for a moment and laughed, said ‘they know me there’, which is when I realised that somehow I’d omitted an entire part of my health journey from our conversation, just out of forgetfulness and definitely not trying to hide anything — ‘by the way, I had corrective cosmetic surgery to fix a misplaced muscle on one side of my head’. Then he looked at my teeth with his torch and I added the usual disclaimer I give the dentist/GP/lucky lovers, ‘if my jaw clicks, it’s fine, it unlocks sometimes because of the surgeries’.

I left the office — was it an office? There was a bed, cupboards, sink, etc. but also a desk in the corner. What would we call that? A multi-purpose space. Check your emails, consult with a scatty, scared patient who’s had more surgeries than boyfriends in her adult life, do some blood tests, dictate a letter to a GP, and then perform a semi-invasive procedure all in one day, and one room. I left the room. I considered rushing out, and back to the car, before my visit surpassed half an hour and I could drive away without paying. But I decided to go to the hospital cafe opposite the entrance, where I ordered a cup of black with extra hot water on the side, smiling while still quietly crying as the ladies behind the cabinet of pastries all tried to treat me like a normal customer/person. I wondered how many people they’d seen and served in this space who were crying, or attached to a bag with tubes, or had missing limbs. They must have seen it all. I held onto that thought as long as I could, because I thought it might stop me feeling too self conscious when I took one of the few available seats in the window, looked out at the trees in the distance and then the netted garden below where birds swooped as busy people moved around in corridors, and I continued to cry and cry and cry. I went through tissues and napkins and then sleeves, uncontrollably and outrageously feeling everything — the place I was in, the times I’d been there before, the way I’d carry myself and protect myself in the words I’d always say and all the things that didn’t quite fit in my mind or work for the life I’d wanted and thought I’d have because wasn’t that my right? I thought of the younger me who’d felt she was special but wasn’t sure why, who had a quiet confidence that she’d always be alright and things would always work out, despite the insecurities she faced as a child and then the rejections she experienced as an elder teen — now living in this aged, broken body that didn’t align with any of it. Many years ago I’d thought, and maybe said to myself aloud, ‘I have been through so much, but I can only take so much.’

Eventually a person in smart clothes and a lanyard came over and asked if I was okay, saying they just ‘couldn’t stand by’ while everyone else ignored me. But I don’t mind. But I didn’t want to be noticed, I didn’t say. I just said ‘it’s okay, nobody’s dying. I just have a lot of things wrong with me.’ The lanyard seemed happy with that, told me to take care of myself, and disappeared. Then I took an ugly selfie for my closest friends, cried for a few more minutes, and left.

Thank you for reading.

Comments

Post a Comment