'Tangleweed and Brine' : A Guest Post

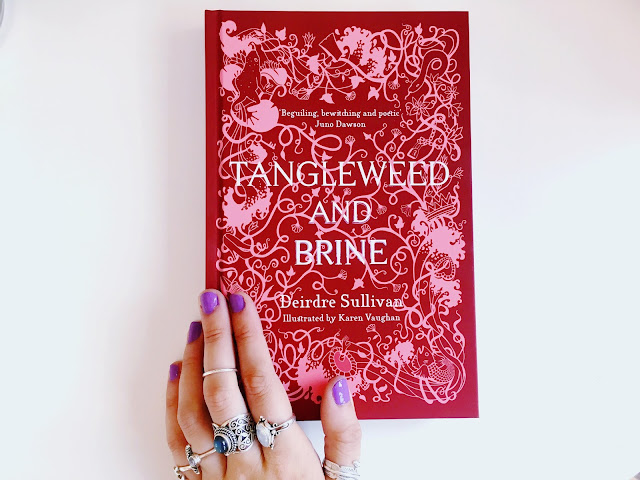

'Tangleweed

and Brine' is the latest novel from the bewitching Deirdre Sullivan.

I read (and blogged about) her painfully stunning YA 'Needlework' this time last year,

and some of her perfectly pieced together paragraphs within that

story of a hideously abused young woman, fighting demons and yearning

for a new life spent making art on others' skin, still sit in the

corners of my mind to this day.

This

gorgeous new hardback is 'A

collection of twelve dark, feminist retellings of traditional

fairytales are given a witchy makeover, not for the faint-hearted,

from one of Ireland's leading writers for young people. You make

candles from stubs of other candles. You like light in your room to

read. Gillian wants thick warm yellow fabric, soft as butter. Lila

prefers cold. All icy blues. Their dresses made to measure. No

expense spared. And dancing slippers. One night's wear and out the

door like ash. You can't even borrow their cast-offs. You wear a pair

of boots got from a child. Of sturdy stuff, that keeps the water out

and gets you around' (so says Goodreads).

I studied fairytales – the traditional, and the twisted – when I was doing my BA in Creative Writing. Our assignment at the end of that Textual Intervention module was to write a creative piece, and I bloody loved making my own bizarre world and inventing creatures and characters within it. I also loved actually studying Angela Carter and her ilk of white witches – and let me tell you, the delightfully wicked Deirdre could totally join those ranks. Her way with words is like no other author, she is utterly incomparable.

Yes,

I am a Deirdre fangirl.

So

imagine my elation when I was given the opportunity to share

something written by this literary heroine!?

Below

is her piece about bodies, and image. (So fitting for this blog,

right?!)

Enjoy!

* *** *

Tangleweed and Brine is

about fairy-tales. Old, dark stories that lodge in our hearts and

throats. That teach us lessons. What it is we want. What women look

like. You can’t discount the drawings in a book. Slender, soft

princesses. Crowns and gowns. Impossibly beautiful. And not in the

way of people you encounter in real life. Waists smaller than necks,

eyes saucer-big, breasts full and legs that ended in the smallest

wisp of foot. This is what the people who get happy endings look

like.

It isn’t true of course.

When I was a little girl, my

mother didn’t wear make-up. She lacked the mobility to touch her

own face. This was good and bad thing. Good, because her skin is very

clear and very smooth. Bad, for obvious reasons. Limits. Itchy noses.

I never thought of her body as different. There was a swing to the

way she walked, got up. It suited her. My mother is full of energy.

Always doing, planning things to do. She never met a challenge she

didn’t face.

Bodies weren’t shameful in my

house. They were functional. They needed to be kept clean, cared for,

nourished. But they didn’t need to look a certain way. I loved to

wear nice dresses as a child. Real floofy ones with skirts that

twirled like peonies when I danced. I had short hair because my

mother couldn’t brush it, comb it. It was very curly, and I had a

sensitive scalp. Even with a bowl-cut I would sob when bristles tore

my tangles apart. I once had a hairdresser break a hairbrush on my

hair. The handle came apart, the top stayed put. My hair is stronger

than a lot of things.

I wonder if my short hair was

what made me aggressively feminine, loving dresses, wanting little

shoes and little bags, crying when my parents threw out a Tinkerbell

make-up set I’d been given for my birthday. I was often mistaken

for a little boy when I wore trousers. Never a lad. Always a “little

boy.” I looked like an angelic little douche. I liked stories where

girls disguised themselves as boys. Viola in Twelfth Night.

George in The Famous Five. Though, George didn’t want to be

girl and people were always reminding her that she was one. I would

have loved that. I hated sports and bravery.

I was twelve years old when I

began to grow my hair out. I was old enough to take care of it

myself. To decide that’s what I wanted. Twelve was an interesting

year in terms of hair. One day, I was wearing a short denim

mini-dress I loved. The son of a family friend looked me up and down

and told me I “needed a waxing appointment”. I looked down at my

legs and felt ashamed. I hadn’t noticed all the hair before, but

now it was a carpet, was a forest. Thick and dark, unwanted and

unwelcome. I hadn’t known that leg hair was a bad thing. My

mother’s legs were not as fuzzed as mine, but they were lightly

sprinkled with soft hair.

And I was used to that.

I didn’t know.

I never felt comfortable with

bare legs again. I wear tights, and if I’m in the pool or at the

beach, I try not to look at my legs. They’re chicken-skin bumpy,

and no matter how often or close I shave, I always miss a spot. It’s

never perfect. I am never perfect. I stopped loving my swimming

lessons after that. My body wasn’t a body. It was an exhibit. On

display.

It

wasn’t functional. It was decorative. My teen years were when I

began to pluck my eyebrows into sleep dark sperm and coat my face and

mouth with pound shop make-up. Not every day. I still do not wear

make-up every day. It feels like putting cream on a scone. Not always

necessary, but it does make the whole thing a bit more fancy. I

wonder if my mother made me that way. Her rebellious body teaching

mine that there’s not one proper way to be in the world. You do not

have to be a certain shape, a certain shade.

When

I tell stories, I think about the body a lot. Not the physical

attributes of my characters, but how they take up space. You can be

very small inside the world and still feel much too big. You can be

large and still feel very small, inconsequential. It is very easy for

a woman to feel both those things, and all at once. In my writing, I

often come back to The Little Mermaid, her unruly body not

appropriate to catch a prince. And once she changed, her form was

still imperfect. She couldn’t speak, the witch cut out her tongue.

That made her pitiable. She had no voice. She had no agency. And was

in chronic pain. Sharpened and blunted at once, she was denied the

happily ever after.

Of

course she was.

She

couldn’t fit into it.

I

don’t think anyone can fit into the shape the world expects. They

grow and shrink, they fall ill or get healthy. It’s like a pair of

jeans you close like a full suitcase round your body. A dress you

push your back-fat in to zip. It taunts you, if you let it. And we

all have our things. We all have those. But I think growing up with

the small shoulders and round hips of a strong disabled woman as my

caregiver built a resilience in me. A core of seeing through the

nonsense. Not in a she’s-my-hero way. Sometimes she is, and other

times she isn’t. She’s a person and I am a person.

We

need to listen to each others’ voices, and experiences.

Resist

the urge to hate the shape we are and love the shape we could be.

The

shape we could be is a lure.

A

lie.

* *** *

'Tangleweed

and Brine' will be appearing on shelves in September.

You

can find it at Waterstones, on Amazon or in The Book Depository.

Comments

Post a Comment